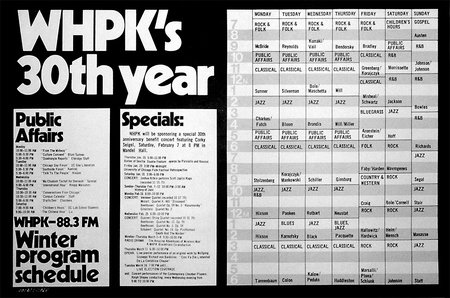

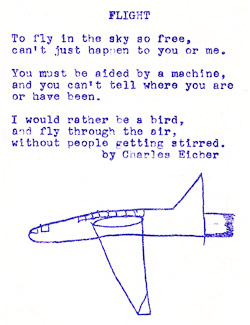

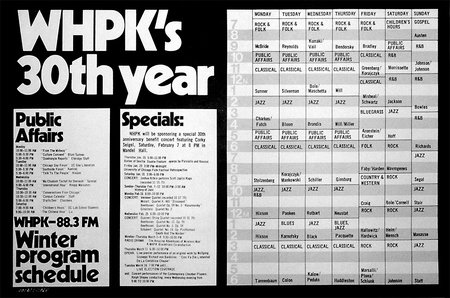

I discovered a copy of my very first commercial gig in graphic design, produced when I was 16 years old. My older sister had a college radio show at WHPK, she came back home for winter break and commissioned me to produce a low budget poster. I put this poster together using the pasteup equipment at my high school newspaper. The remarkable thing about this poster is that it was all done by hand on a paste-up board, no computers, no digital typesetting. You can click on the poster to see a larger image pop up.

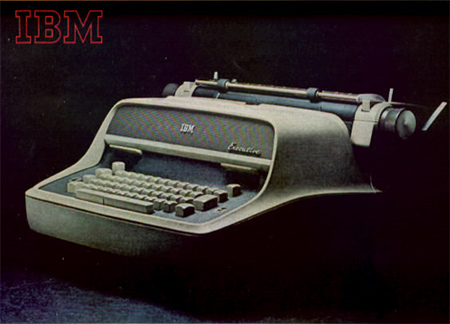

This poster was produced using Chartpak type, rolls of tiny "hairline" tape, wax adhesive, some darkroom work, and an IBM Model C Executive typewriter. The Model C was a wonderful typewriter, it could do proportional spacing and if you used a carbon ribbon, it had almost typeset quality. Almost. Someone donated an old beat up Model C to our school, it was obsoleted when the Selectric was released. Our Model C's output was sometimes shaky, but it was the best we could get for free. I had a hard time finding a decent pic of the old Model C Executive, it was released in 1959 so it's way before the internet.

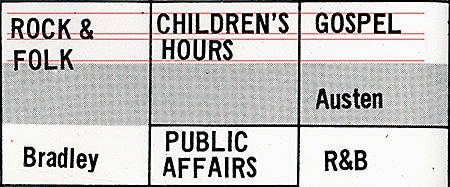

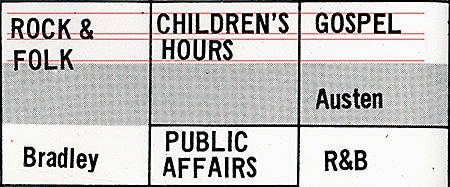

The Model C's typesetting could be frustrating, particularly since it didn't have very good vertical precision. The sorts of things the Model C did would be intolerable to anyone using modern computer design programs. Here's a good example. I scanned a closeup of the schedule, you can see how hard it was to align the type and have consistent leading (the vertical space between lines).

I marked the correct type baselines in red, you can see how "ROCK & FOLK" does not line up right. Even the best typesetting (in the "Children's Hour") is kind of shaky, with a slight slant. Some of this type is slightly crooked because it was cut out and glued in place. This is how the grid system started, you had to lay down small pieces of type into a layout and everything would be hopelessly out of alignment if you didn't line everything up on the grid. But even crooked type can be made worse, the letters in the word "Bradley" keep getting lower and lower, it looks like the paper was slipping in the typewriter. And the A in Public Affairs is chipped off. Sometimes the letters would flake off, the carbon ribbon printing was very delicate. We worked for hours over these pasteups, moving things around and reworking them. It's a miracle things stay lined up at all.

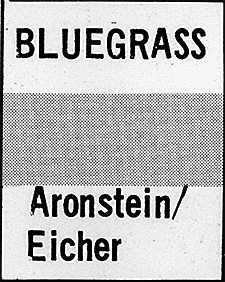

But I'm not taking responsibility for the poor type even though this is my poster, I think my sister did most of the typing while I worked on the headline type and layout. So I'll get even with her and release a skeleton from her closet: she had a bluegrass music college radio show. Today, she will deny she ever had any interest in bluegrass music and was an avid bluegrass musician. But I have the evidence.

You can see another common layout problem in the upper left corner of that box, the corner is open. All the lines were produced with rolls of Chartpak Graphic Tape. This is hairline width, I think it's 0.25 points. The tiny tapes were terribly difficult to work with, you had to stretch the tapes over the layout board, align it to the faint blue grid lines, carefully press them into the paper, and cut the ends with an X-Acto knife. Corners were especially difficult. If the layout board was mishandled, the tapes could pull apart and leave open corners.

But enough about the problems, there are some good features to this design as well. The headlines in Kabel Bold type were all done by hand with Chartpak "rub-on" transfer type. The letters came on plastic sheets, you moved the sheet into position on paper and rubbed the plastic sheet with a blunt tip "burnisher" to transfer the letter onto your paper. It was hard to make good rub-on type, but this is an excellent job. Wow, look at that tight kerning! And it was all done by eye.

I liked to put the type on clear acetate and then enlarge it in the darkroom. I could enlarge type to whatever size I needed, even advanced phototypesetting came only in fixed sizes. Nowadays we take resizing type for granted, we just use the computer and drag the type block until it's the size we want. But back in the 1970s, that meant printing on photo paper in a darkroom and developing it in trays of chemicals.

The core idea of this poster was a chronological layout, using gray stripes to guide the eye across the grid. Today this design is known as "zebra stripes," it's very common, it is even used on computer screens to display long file lists. I got the idea from "green bar" computer paper, it had green zebra stripes to guide your eyes across 14 inch wide paper.

We called the little graphic device on the left a "puppy." I made design elements like this for our high school newspaper. One day I gave my finished artwork to a guy working on the newspaper layout and he said, "slap that puppy on there!" So that name kind of stuck to it.

But I digress. That artwork is deceptively complex, it had to be produced on 3 different layout sheets. Each sheet had to align precisely with the others and you could not see how it would look until the layers of artwork were etched into a printing plate.

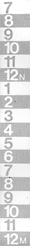

The dark bars and dark numbers were laid out on one sheet. Then a second sheet was an overlay with the type that would be "knocked out," putting the white type in the dark bars. The camera operator who turned this artwork into a printing plate had several steps to perform. The layers were photographed on separate negatives at full size. Then the films were overlaid and the numbers "subtracted" from the bars on the other sheet, and halftone dots added to make it gray. Then that negative was positioned on the main poster design on the third layout sheet. That sounds like a lot of work, it was, but we did this all the time with manual layouts. So when you use Photoshop and you see confusing commands like "Subtract Layer," this is where that stuff all came from. It was standard graphic arts technique.

The final step was to print the poster. I used the local print shop that we used for our high school newspaper. They had a beautiful Miele sheet-fed offset press that was probably manufactured in the 1920s. The poster was designed to fit exactly twice in the maximum paper size of this press, so the sheets could be chopped in half. I picked a glossy, stiff poster paper for this job.

I went back to the print shop to see if the printing plates worked as I had designed them. Surprisingly, they had already printed the whole job, but on the wrong paper, on the wrong press. But the posters looked great, I took one sheet as a proof. They printed on much larger sheets on a more expensive press than I could afford, they upgraded my job for free. But the larger press used bigger sheets of paper, that's why I targeted the smaller press. Now the posters had large white edges that would all have to be chopped off, 5 precise cuts in the big cutting machine instead of one. I didn't care much about that, they didn't charge extra for the cutting, but it was just another step where errors could occur. I loved the thick, matte paper they used, I told them to not reprint the job on the right paper, I'd take the job as-is. But when I came back the next day, they had reprinted the whole job on the glossy paper and discarded the matte version. So this press proof is the only remaining matte version.

The final press run was printed, cut, and wrapped in brown butcher-paper bundles. The whole job was a stack of paper about two feet high. It was amazingly heavy. I loaded the bundles into my sister's trunk so she could drive them back to college, I could see the rear end of her car sag slightly under the weight. She told me that everyone at WHPK loved the poster. I suspected they liked it mostly because the design was so elaborate for such a low budget. Most of the money went to the printer. I can't remember the exact budget, but I vaguely recall the printing cost about $100 and I think I made about $25 for myself. The cost of materials couldn't be more than about $3, but I don't recall exactly.

Well that was quite a trip down memory lane. It is amazing how much I remember about this specific job, considering it was 37 years ago. And then I realize, I've been working in print and design for over 37 years! I often think about how many obscure technical skills were required to manually produce these projects, and how those

tools and methods are considered a lost art in the modern digital design world. But these primitive skills were the foundation of my lifetime career in graphic design and printing.

Printing and design has changed so much over the years, but I can never really get far from my roots. Coincidentally, I now live next door to the old print shop site. They disbanded long ago, now it's a hardware store. I am writing this article about 150 feet from where this poster was printed.